This post is hard to write. I’m missing the tree. I’ve realised that we have a relationship. Like any relationship, it’s been building slowly over time. There’s a level of trust, companionship. It’s two-way. But I need to be there to enable it to grow. We can’t audio or video call. I’ve tried having a conversation at a distance, but she’s clear, wait until you’re back. How can I? I’ve come to rely her wisdom.

As always, reality is more complex than one thing. It’s also fun being in town; spending time with friends and family, hanging out with the grandchildren. Nature is less present though. She’s there on the edges; mangroves thriving in the sediment of the city harbour estuaries; regenerating native bush meeting the black sands of the wild West Coast beaches. Pōhutukawa trees, clinging to the nooks and crannies between the land and the sea, delineating the shores of Tāmaki Makaurau, the Māori name for Auckland.

Tāmaki means “desired by many” and refers to the abundance of natural resources, strategic land forms and portage routes, the natural kai (food) that thrived in sparkling waters of the Waitematā Harbour, and the arable land that could be cultivated for crops. Of course, the early European settlers also desired these resources. Today Auckland is home to a culturally diverse population made up of over 120 different ethnicities. All attracted to this place of opportunity. Not without cost to the natural environment.

However, as our tree on Waiheke so sagely observed, while we humans can be destructive, we can also be aware. Western Park, close to where we are staying in town is an example. It runs off bustling Ponsonby Road and is well loved by inner city dwellers and visitors alike.

Western Park, from the top and from the bottom. Photos JF 11.03.2025

In 1873 a design competition was won by architect and surveyor William Hammond and orchardist and gardener J.C. Blackmore for what was then known as City Park. In a move that now seems prescient, they proposed the park could act as a “lung” for the city, freshening the air for its inhabitants. The extensive planting of 1100 exotic trees made it an arboretum – a botanical collection of mostly non-local species – a popular concept at the time. More recently, as we’ve become even more aware (some would say woke!) native ferns and grasses have been planted along the valley floor and native trees and shrubs are dotted amongst the original exotic pines, camphor laurels, cypress, oaks and Moreton Bay figs.

Winning design for City Park, Auckland, 1873. Auckland Council Libraries − Tāmaki Pātaka Kōrero o Tāmaki Makaurau, Sir George Grey Special Collections

Reference: NZ Map 4686

Since we have been in town I have been looking for a tree to talk with. Most afternoons we go for a walk in Western Park. I have lived near and around this park on and off since 1980 when I first came to Auckland. I brought my children here as toddlers and pre-schoolers to play on the playground, run down the grassy slopes and climb in the trees. We have had hours of fun here with our grandchildren, watching them whizz down the big tunnel slides, swoop on the flying fox, race toy cars down the asphalt paths and climb over the sculptures of old buildings.

John Radford Sculptures of buildings demolished in the 1980s. Photo JF 19.07.2023

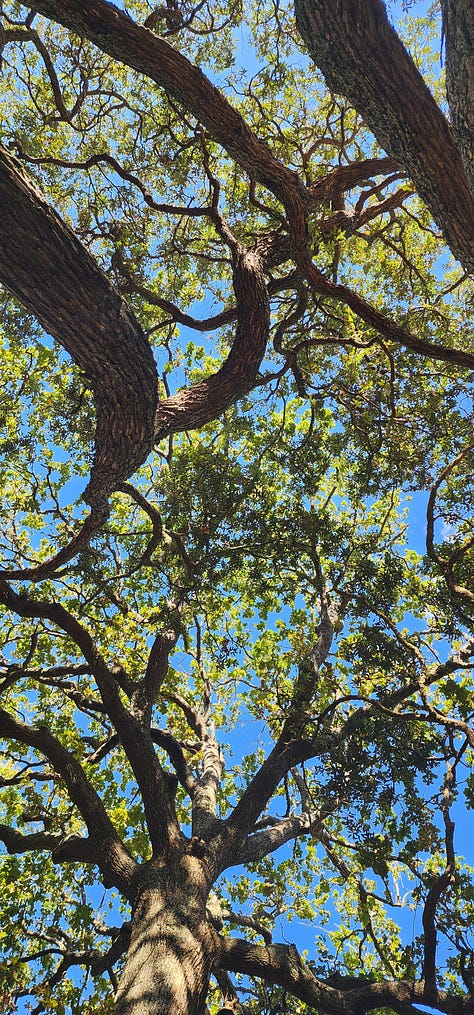

But I haven’t really tried talking to any of the trees until now. As we thread our way around the paths, up and down the gullies, the towering giants in our midst seem strangely quiet. Actually, other than the sounds of people and traffic there is not a lot coming from nature. Perhaps some wind rustling the branches and the odd bird call. I had spotted a sizeable pōhutukawa tree on a previous walk and this time I stopped to see if she/he/it? was willing to talk with me. I leaned against one of its many trunks, standing astride the roots woven along the raised ground by the path.

As I gazed upwards I could see the branches and leaves of the pōhutukawa were intermingled with the branches and leaves of the old oak tree planted on the opposite side of the path. Their crowns were meeting above, sharing the sun and light. I imagined their roots inter-connected beneath the path, sharing the nutrients in the soil and the rain water as it seeped down the gully slopes. I was musing about the native and the exotic sharing space, quite comfortably it seemed. What did the pōhutukawa really think? Then a voice, you’ve gotta get along with your neighbours. That was it. There didn’t seem to be any further conversation to be had that day. I felt joyous though, it was possible to talk to other trees. I resolved to come back the next day and see what unfolded.

So dutifully, I returned today. This time I climbed up into the nest-like bowl just above the ground in between the tree’s many trunks. I was very conscious of other people in the park – what would they think of this 70-year-old climbing up in a tree and perching there like a kid? Too bad, I did it anyway. I liked the feeling of youthfulness it gave me, even though I was way more awkward in my clambering up and attempting to get my uncoordinated body comfortable than any child would be! After a bit of manoeuvring I finally found a spot that was semi-comfortable with my back and head against a branch and my bottom lodged in a crevice between the trunks.

I didn’t expect what happened next. A flood of anger. It was clearly coming from the tree, but who was it directed at? Not you specifically, came the answer, the tree pre-empting my question. Humans have taken the liberty of tampering with so much, and are so unaware of the consequences of their actions. Look at this park. We do our best as trees here, but it’s not natural. Where are the saplings? They are all mown away. The stream has been drained, the natural water courses re-directed, sucked up by humans. Only now in some areas of the park are the branches and leaves that fall being used as mulch to replenish the nutrients in the soil, but not around me or my mates here. The trees are planted too far apart and not with our natural neighbours. We do our best to get along, we have to. Community is everything, it’s survival. We need each other. And look further, around us, the man-made activity, the din of the city. We have to co-exist, we have no choice, but this is not how and where most of us would choose to grow. When I was a seedling, the sea was closer, I could see it, feel the salty air. I’m a pōhutukawa, I love to be on the coast. You humans reclaimed the sea and now it’s far away and the city is all around.

Oh, no wonder they’re silent and angry I thought. I felt chastised, guilty on behalf of the human race. The tree hadn’t quite finished though. I’m helping you to become aware, it said, being woke isn’t a bad thing. Ha! It’s picked up on the lingo of the current zeitgeist.

I felt grateful that the tree had been willing to share, even though what it had to say was hard to hear. I wondered how old it was. I guessed from its size that it pre-dated the arboretum being planted, so more than 150 years old? Regardless, it had seen a lot. City trees are different I thought. Initially less friendly and more guarded, but once warmed up, very straight talking.

Much to ponder. Where to start? I remembered my Waiheke tree’s wise advice – don’t try too hard, just relax. I do like my city tree’s take home message though, it’s ok to be woke. Diversity is our reality, we need to get along. Ultimately it’ll be our strength. Community is everything, it’s survival. Embracing it all, each other, our animal bodies and our inter-dependence with the natural world.

Thank you city tree, I’ll be back.

You are not alone in having a relationship with a tree. I've run across several people who do. I am one also, although not a particular tree. Some trees just want or need to communicate with us, the race that is so willing to destroy them.

Yes we just need to be willing to listen. What have trees communicaed to you? Does there seem to be any theme? I was also surprised to feel emotions from trees as I hadn't expected that!